BEARING WITNESS

The ethics and practice of conflict reporting in South Sudan

Atrium Gallery, London School of Economics, 18 - 29 March 2019]

Conflict reporting is a hard job, done in hard places.

It’s challenging both practically, in the face of

governments and armed groups intent on concealing

acts of violence, and ethically, in that it frequently

involves watching and recording the suffering of

others. What might justify professional conflict

reporting as something other than voyeurism, and

what makes it so hard to do?

This exhibition explores some of these themes in terms of

the work of journalists covering South Sudan’s ongoing

conflict. Based on over forty interviews with journalists

and fieldwork in the country’s capital, Juba, and the UN’s

Malakal protection of civilians site, it explores two

questions common to many forms of conflict reporting

across the world.

Why is it so hard to cover conflict? In South Sudan, a

combination of forces combine to make the work of the

journalist almost impossibly difficult. Many of the

constraints are particular to the country (though not

unique to it), such as poor infrastructure, danger and

state repression of the media. Beyond this, though,

changes to journalism more generally have created levels

of precarity that have made it virtually impossible for

journalists to work full-time as correspondents.

What justifies watching the suffering of others? As Susan Sontag famously reflected, “Perhaps the only people with the right to look at images of suffering of

this extreme order are those who could do something to alleviate it - say, the surgeons at the military hospital where the photograph was taken - or those who

could learn from it. The rest of us are voyeurs, whether or not we mean to be.”

If we want to hold onto the conviction that watching the suffering of others, as journalists, is something other than voyeurism, it is worth considering what

a defence of such watching might consist of. What might make the gaze of the journalist not merely ‘not voyeuristic’, but even morally

praiseworthy – a form of bearing witness?

ACCREDITATION & CONTROL

The Media Authority

For journalists coming to work in South Sudan from outside the country, the Media Authority of South Sudan is a significant

obstacle to free reporting. On paper, the Authority is meant to serve as an impartial ombudsman-style regulator - in terms

of the 2013 Media Authority Act that established it, “no government license shall be required from any person practicing

journalism as a profession” and “all print media shall be self-regulating”. In practice, media regulation is practiced in

cooperation with the country’s feared National Security Service and the harassment and control of journalists is a too-frequent occurrence.

Reporting in South Sudan as an outsider requires a letter of invitation from a South Sudanese individual or organisation,

and visas are only issued after the Media Authority has conducted a background check that includes searching a journalist’s

past reporting for any articles critical of the state. On arrival, further accreditation and filming licenses must be applied

for, and travel out of the capital is subject to approval by the National Security Service.

Barriers to Journalists

Beyond the bureaucratic hurdles of the Media Authority, reporting in the country requires navigating many additional obstacles.

Safe travel outside of the capital is extremely limited, and accessing remote towns and protection of civilians sites may require

flying. Flights with the UN peacekeeping mission (UNMISS) may be free, but are granted at the UN’s discretion. Flights on the

Humanitarian Air Service (UNHAS) can cost up to 250 USD each way, and commercial carriers are limited and often unsafe. Many

flights’ passenger lists are also screened by the National Security Service, who may remove people at their discretion.

Increasing pressure on the budgets of both international and South Sudanese news organisations has meant that working as a

full-time journalist is increasingly difficult. Many journalists working for South Sudanese publications may earn well below a

hundred dollars a month as a salary, making side-work for NGOs (or in other industries altogether) commonplace. Foreign correspondents

are not exempt from these pressures – rental of a place to stay in Juba can easily run to 1,200 dollars a month or more. Many

of those interviewed expressed the view that the economics of the system are fundamentally broken.

Relying on NGOs

Safe reporting will often mean effectively embedding inside the security and logistics infrastructure of one of the few organisations that have a presence in remote field locations.

Such positions require compromises, in which journalists may find themselves subject to movement restrictions and reliant on translators and other intermediaries for access to the area.

Daily Routines

Much of the daily work of ‘conflict reporting’ is in fact fairly banal. Given the risk and expense associated with travel, much is done in the capital, Juba, or over the telephone.

Inside Juba, daily reporting consists of a regular beat of attending court cases, briefings, or press conferences run by the government and major NGOs and obtaining commentary or interviews

Accommodation

Accommodation in the field, such as on an UNMISS base in Malakal’s Protection of Civilians site, consists of converted shipping containers containing a shower, bed and a desk.

Outside temperatures during summer can exceed 42 degrees, and food and water are in limited supply. In general, the UN tends to limit journalists’ stays on-base to a few days, making it challenging to collect the material required for longer, in-depth reporting.

Accommodation

Reporting on conflict is inherently dangerous, with continual compromises between what is possible and what is affordable. Body armour,

hostile environment training and security arrangements on remote assignments are now practically unaffordable to nearly all journalists

in the country. NGOs fill in some of the gaps with safety training and grants for reporting projects where they can, but most publications

simply cannot afford the costs of appropriate safety and security anymore. The result of this dilemma is that hard choices must be made

between taking risks and making ends meet.

ON THE JOB

Reflections of journalists working in South Sudan

“Why do we do what we do?”

“Yeah?”

“Because it's tremendously fun. To begin with, because holding a notebook means you can go somewhere you shouldn't be and ask

people questions that you ordinarily wouldn't be allowed to ask. And because it satisfies, kind of, your curiosity about the world.”

“Yeah, well, so photojournalists manage to carve out this, this niche that doesn't seem to work for print, which is that you're

somehow permitted to go and literally work for an NGO, get paid by them, and then flog those pictures to the media, and that's

not a conflict of interest. Somehow."

“I'd say there are two factors now. One is safety, and the other is money. Because news outlets are less and less happy about

supplying either of those things. And they usually come hand in hand, because the more dangerous the situation is, the more

expensive it is to operate. So you hear a lot of 'oh we love [X], we love the story, we're really interested, like, we'd love

to see material when it's finished.'”

“...journalism in South Sudan, there is no money. Most of our journalists, they are suffering. I mean, they don't have transport,

some of them work [elsewhere], they move food from their houses, they don't have offices to operate. Their living conditions are

not that good. And there is no motivation factor that can, that, that is in place, let me say, that can help some of these journalists.

You find that the journalists have depression. A depression to, to practice journalism. But the environment itself will force them,

financially, will force them out. To go and look for other opportunities outside. So you may find that the journalist, he may come

in, practice journalism, learn the skills. Six to seven months, one year, he's out.”

“For me, let me just take the example for myself, I do it from indoors, yeah. Just call, make phone calls and then get some people,

but online and then you talk to them. Either you visit them, you can visit them to their offices, you talk to them, you know, get their

interviews, but sometimes it's very risky to, to do investigative time [on] a story. It's not easy here. Because once they get hold of

you, you are dead. You expose anything which is [of concern to] the system, you are dead.”

“a lot of the time, you know, these guys who are training you, ex some sort of special forces type people. And really, really what they're

talking about is Iraq and Afghanistan, not here. They've never been here. They don't know what it's like. They're like, you know, if you're

going to a hostile area, you must hire two vehicles so you have a backup, and you must have, like, your personal security adviser with you.

I was like, you've clearly never been a freelancer in Africa. We're lucky if we can afford one motorbike. Let alone two armoured cars.”

“If you had been here, say, January 2016, 2017, before the media authority was actually, like, up and running, you would find this place,

like 80%, 90% journalists. Logali's literally called the journalists’ hub... It's very close and, again, Logali's amazing.in terms of protecting

journalists. You know, they stood up for journalists in July, they, they really care about, they understand that, you know, our base here is for

journalists, and they're we're for them. But now it's not the same. You can literally count, so now you can literally count on one hand the number

of journalists in town, right?”

“..immediately for a girl, like what you think in those situations is very different than for a guy. But also it can be beneficial, because there are

times when we are at checkpoints, they would see my arms, so they would look up, and then they would see a female mzungu or whatever, kawaja is what

they call it, and they would be much more relaxed with me, than with a guy, in some cases. But then at checkpoints, there'd be times where they'd try

to make me get out of the car and no-one else, and those were really concerning as well, at night. So yeah, it just like, It changes the way you think

about where you can go safely, and what risks you are willing to take.”

“For me, I went because I believe in journalism as like a tool to make better societies, and so I went knowing that I would do journalism and then training,

because I believe in that but then the reason that I, I am still working on that is like, once you are there and you know people and you are invested,

and the conflict, and also you have put yourself at risk in order to be, you know, you have become a part of it, it's really hard to leave it behind.”

MORAL WATCHING

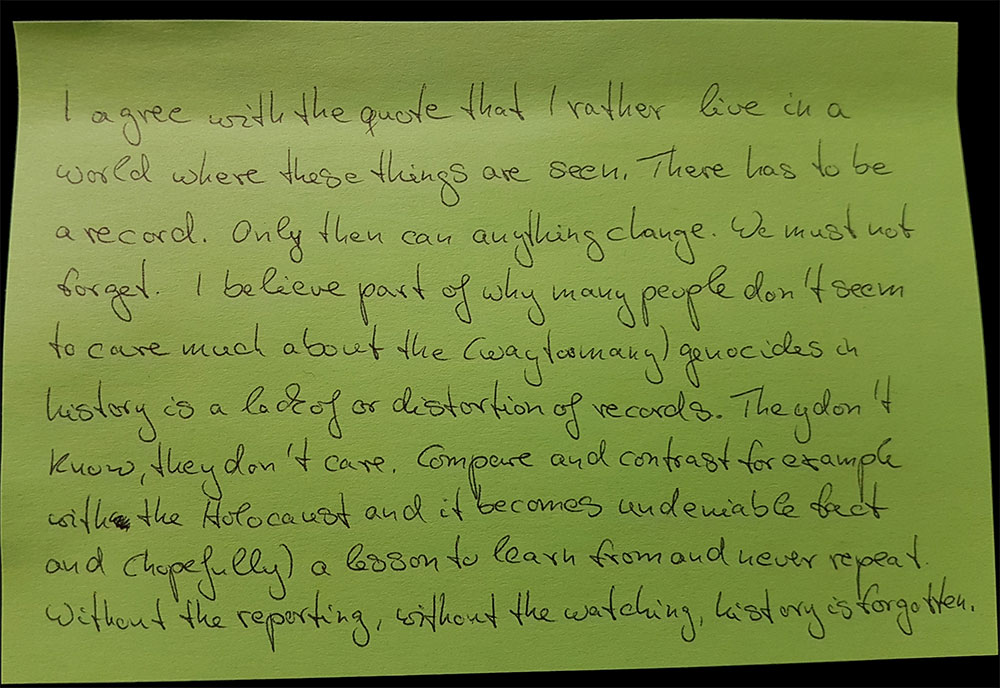

“I mean maybe it's just a personal thing, but I can't think of anything worse than something terrible happening in the world and nobody else knowing about it.

Or no-one... or, or it being forgotten in history where there being no record of it. I think it's just my personality, I'm a collector of things. And I, I,

that's just part of my personality, but I can't think of anything more unjust than someone, or a group of people, or whoever, having to go through something

really terrible and no-one else knowing about it. And that's where I think that whole concept of bearing witness is really important.

And I know it's a phrase that my colleagues use quite a lot as a way of justifying their work, but I, I sincerely believe it. I really think it's important.

And, you know, a photo's not going to save the world, by any stretch of the imagination, but I would rather live in a world where there is that photo,

than where there isn't.”

Interview respondent

Have feedback on the exhibition, or want more information?

Email the organiser at r.j.stupart@rug.nl

Exhibition supported by